Demystifying Bank Risk Sharing Transactions – Part 3

In Parts 1 and 2 of this four-part series, we introduced the Risk Sharing Transactions (RSTs) banks utilise to optimise their Tier 1 Capital (CET1) ratios in accordance with the risk-weighting regime set by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in order to meet the capital ratio requirements mandated by the Basel III framework.

In this Part 3, applying what we set out in Parts 1 and 2, we’ll explain the economic rationale for the banks that utilise RSTs.

XYZ Bank – A Hypothetical Study

XYZ Bank is a large, systemically important European bank headquartered in Germany. With core capital of €75 billion and risk-weighted assets of €500 billion, its CET1 ratio of 15% exceeds its minimum CET1 capital requirement of 10%. Despite this healthy capital ratio and like most of its peers, its shares trade at a price-to-book ratio significantly below the real market value of its assets. The bank announced a target return on equity (TRoE) for 2024 of 14%.

Under pressure to expand its lending activities while maintaining dividend payments and having rejected the options of issuing either new shares (dilutive, given the low price-to-book ratio) or more AT1s (too expensive), the board has turned to RSTs to reduce RWA and thereby improve its CET1 ratio. Not wishing to expose itself to the publicity and uncertainty of a widely syndicated RST, the board opts to issue in a bilateral synthetic RST with a single investor, CRT Fund.

XYZ Bank approaches CRT Fund with a ‘blind’ €10 billion mixed pool of assets consisting of, among other things, loans to small and medium enterprise (SME) and mid-cap companies, commercial and retail mortgages and consumer finance infrastructure loans, to both its core customers in Germany and borrowers in other regions.

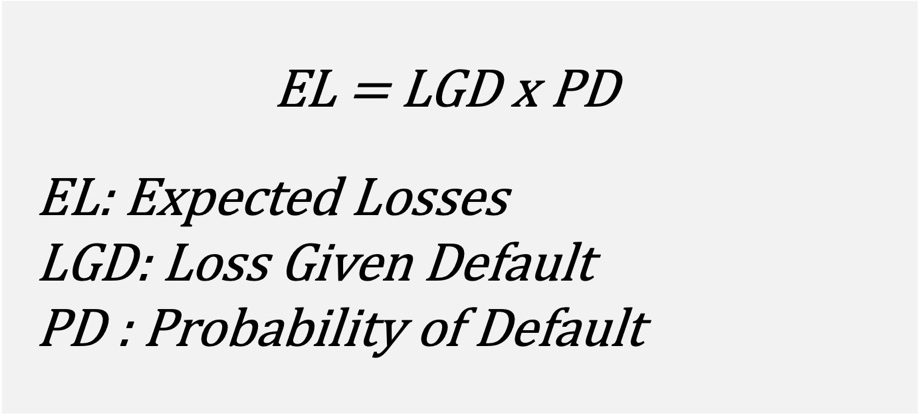

Together, XYZ Bank and CRT Fund exclude certain loan types, loans to certain sectors and all non-German borrowers, leaving a €2 billion portfolio of loans to German SMEs and mid-caps, with a weighted average life (WAL) of 3.5 years. XYZ bank uses an internal ratings-based approach to calculate portfolio risk weightings under BIS rules. The bank shares with CRT Fund the loss given default (LGD) and probability of default (PD) for each loan in the portfolio, allowing CRT Fund to calculate the expected losses (EL).

The portfolio has an LGD of 30% and a PD of 1%, so the annual EL is 0.30% (i.e., 30% × 1%).

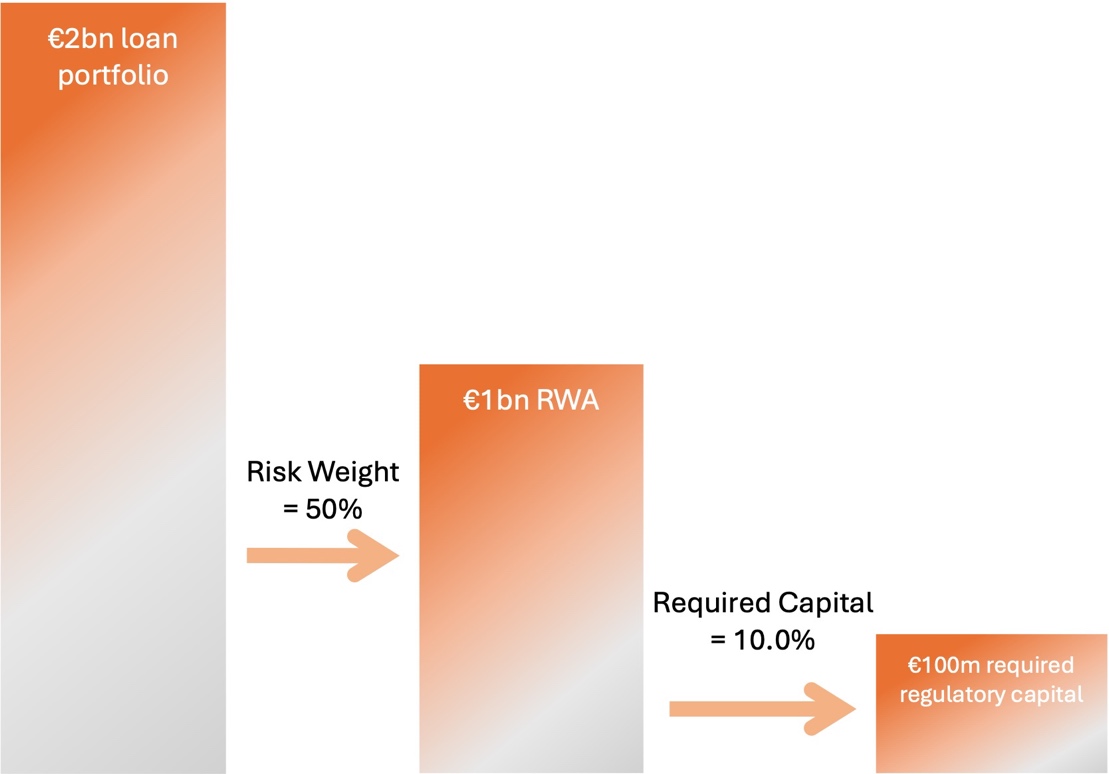

Pre-RST, the portfolio has a risk weighting of 50% under BIS rules. The portfolio therefore comprises €1 billion RWA (50% × €2bn), against which the Basel III framework requires the bank to hold €100 million capital (i.e., 10% × €1bn).

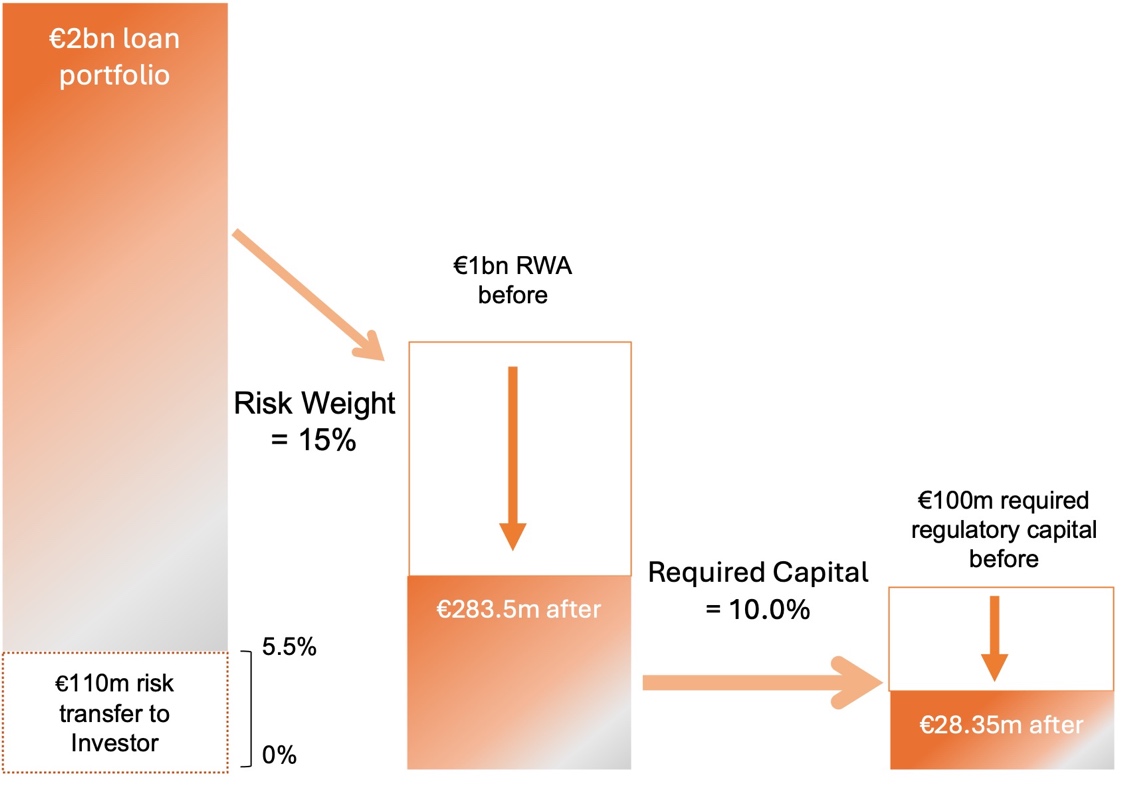

XYZ Bank and CRT Fund elect to structure a First Loss RST with a 5.5% detachment point, meaning that, subject to Basel III’s 5% risk retention rules, CRT Fund as the RST investor will assume the risk of losses on the first €110 million (5.5% × €2bn) of this portfolio. The portfolio amortises over time as the loans are repaid or prepaid and by year four, the portfolio is expected to be less than 10% of its current size, so the parties agree that after 3.5 years, coinciding with the WAL of the portfolio, the bank can redeem the transaction (also known as a time call) and repay the remaining investment. We can therefore say that the expected losses of this €2 billion portfolio over the expected life of the RST will be in the order of €21 million (i.e., €2bn × 0.30% × 3.5).

With the RST investor assuming the 0–5.5% junior, or equity, tranche of risk (or €110m first loss), the remaining 94.5% senior tranche risk (or €1.89bn) is retained by XYZ Bank. The risk weight of this retained tranche is 15% under the BIS rules, against which the Basel III rules require the bank to hold 10% equity. In other words, the portfolio now comprises RWA of €283.5 million (€1.89m × 15%), against which the bank is required to hold €28.35 million capital (€283.5m × 10%). The RST has therefore released €71.65 million capital (€100m – €28.35m).

Following the example we used in Part 1 of this series, an RST has transformed the regulatory capital requirement for this portfolio from this:

To this:

In order to release €71.65 million regulatory capital, XYZ Bank agrees to pay CRT Fund a quarterly coupon equal to Euribor + 10.45%. In year one, ignoring the Euribor funding cost and any losses on the portfolio, the bank will pay CRT Fund a coupon of approximately €11.5 million (€110m × 10.45%). If we now factor expected losses (losses borne by CRT Fund as the RST investor) into our calculation and assume the portfolio amortises at a constant rate, the bank will pay over the 3.5-year expected life of this RST a coupon of approximately €40 million, i.e., the product of the €110 million tranche size, the 10.45% coupon and a little under the 3.5-year WAL of the portfolio to take into account expected losses in the portfolio over that period.

Does this make economic sense for the bank? In order to answer this question, we need to compare the cost paid by XYZ Bank for this RST to what the bank expects to earn on the freed-up capital. One commonly recognised proxy for what a bank expects to earn on any capital is its TRoE which, in the case of XYZ Bank, we’ve stated to be 14%.

To calculate the cost of regulatory capital released, we need two components:

- the regulatory capital released by the RST; and

- the implied RST coupon on the entire loan portfolio.

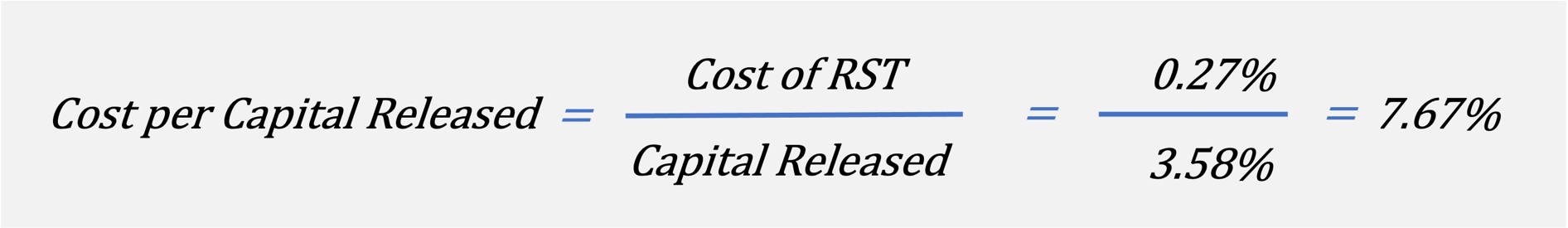

As we showed above, this RST has released €71.65 million capital (€100m – €28.35m), or 3.58% of the entire €2 billion loan portfolio.

The cost of the RST as a percentage of the entire portfolio is the coupon (10.45%) multiplied by the tranche (5.5%) after deducting the EL (0.30%). We deduct the EL because these are losses which, post RST, are borne by CRT Fund and no longer by XYZ Bank. 10.45% × 5.5% – 0.30% = 0.27%.

Having determined the capital released and the RST cost, both expressed as percentages of the entire portfolio, the cost per capital released is a simple calculation:

This RST releases €71.65 million regulatory capital at a cost of 7.67%, whereas the bank expects to earn nearly double this amount (i.e. the TRoE for 2024 of 14%) on the released capital.

The net economic benefit of this RST for the bank is stark, even before considering further potential benefits such as increased banking activity, shareholder dividends and a higher CET1 ratio bringing potentially lower funding costs. Banks utilising RSTs to release regulatory capital recognise that these benefits accrue regardless of the actual performance of the portfolio, so they don’t need to anticipate losses on the portfolio in order for RST issuance to make financial sense. If anything, it would be detrimental for a bank to select sectors or loans for RSTs in which it anticipates losses because, over the medium to long term, banks benefit from improved RST performance leading to lower coupons on subsequent RSTs.

We will expand on this last point in the fourth and final part of this series on Demystifying Bank Risk Sharing Transactions: Key Considerations for Investors in RSTs.

For more information:

Email: laurie@christoffersonrobb.com