Demystifying Bank Risk Sharing Transactions – Part 2

In Part 1 of this four-part series, we introduced Risk Sharing Transactions (RSTs) and the vital role they play in helping banks to optimise their Tier 1 Capital Ratios (CET1). In concluding Part 1, we emphasised that RSTs do not depend for their efficacy on complex structuring; rather, they represent the effective application of the risk-weighting regime set by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) and the capital ratio requirements mandated by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision reforms, more commonly referred to as Basel III.

In this article, we’ll focus on the regulatory regime underpinning RSTs and their importance for the healthy functioning of the European and US banking systems in particular.

What is Basel III (and what happened to Basel I and II)?

The Basel I, II and III rules refer to international regulatory frameworks established by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision to strengthen regulation, supervision, and risk management within the banking sector.

The Basel Capital Accord, subsequently referred to as Basel I, was launched in July 1988 in the aftermath of, and with added impetus given by, the Latin American debt crisis of the early 1980s. Its origins, however, can be traced back further, to the 1975 Basel Concordat, which sought to improve the quality and consistency of banking supervision worldwide and provide a forum for communication between Committee members – initially comprising representatives of central bank governors from G10 countries, but since then expanded to over 45 members from 28 jurisdictions – on supervisory matters.

The Basel Capital Accord, which focused on credit risk, capital adequacy and differences in capital requirements between members, called for a minimum ratio of 8% capital to risk-weighted assets and introduced a system of risk-weighting for different categories of assets to reflect the varying levels of associated risk. It was always intended to evolve over time and was duly amended several times in the ’90s. Notably, in 1996, an amendment allowed banks for the first time to use internal models for measuring market risk and the resulting capital requirements.

As markets evolved and banks grew in sophistication, so the need for a revised framework became more urgent and accordingly, the reforms known as Basel II followed in 2004, comprising three pillars:

Basel II sought to establish a more sophisticated approach to calculating capital adequacy requirements by quantifying, alongside credit risk, the operational and market risks to which banks were exposed. It also introduced the standardised and internal ratings-based approaches to calculating credit risk and associated capital requirements. Modifications to Basel II were rolled out in July 2009 to address certain perceived shortcomings in the area of market risk and, more specifically, an immediate need to ensure adequate capital requirements for bank trading activities exposed by the global financial crisis of 2007–2009 (GFC). These reforms are often referred to as Basel 2.5.

Basel III, first released in January 2016 and then revised in January 2019 in what became known as Basel III Endgame, was a more comprehensive response to the GFC, aimed at enhancing the resilience of not only banks but the financial system overall. More specifically, Basel III aimed to correct obvious deficiencies in both the pre-crisis (Basel I) framework and the Basel II/Basel 2.5 reforms.

Alongside curtailing the use of internal models for assessing credit risk first introduced by Basel II, key reforms introduced by Basel III included:

- Higher core capital requirements as measured by the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR);

- New liquidity standards, including:

- Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), requiring banks to hold sufficient high-quality liquid assets to cover total net cash outflows over a 30-day stress period;

- Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) to ensure longer-term stability by having banks maintain a stable funding profile in relation to their assets and off-balance-sheet activities; and

- Leverage Ratio requirement of 3% as a further backstop to risk-based capital ratios.

- Additional capital requirements for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs), to address the risks they may pose to the financial system should they fail.

What interests us most when discussing RSTs are the bank capital requirements; we’ll focus on those for the remainder of this article.

What constitutes “core capital”?

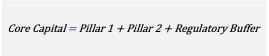

In Part 1, we established that the Core Equity Tier 1 Ratio, or CET1, is calculated as follows:

The numerator, Core Capital, is calculated as follows:

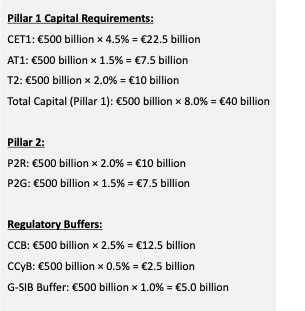

Pillar 1 is the baseline capital requirement that all banks must meet and may be broken down as follows:

- CET1 capital minimum requirement: 4.5% of RWA.

- Tier 1 capital minimum requirement: 6% of RWA inclusive of the 4.5% CET1, with an additional 1.5% that can be met with Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital.

- Total capital minimum requirement: 8% of RWA including 6% Tier 1 capital (CET1 + AT1) and an additional 2% that can be met with Tier 2 (T2) capital.

Pillar 2 comprises two components:

- Pillar 2 Requirement (P2R): An additional amount imposed by the regulator based on the specific circumstances of the bank. P2R is designed to cover risks not fully addressed by the Pillar 1 requirements and can be partly satisfied with AT1 and T2 capital, not solely with CET1.

- Pillar 2 Guidance (P2G): A number supplied by the local banking regulator to ensure that stress tests don’t hit the 4.5% regulatory minimum plus Pillar 2 Requirement.

The final element, the Regulatory Buffer, breaks down as follows:

- Capital Conservation Buffer (CCB) of 2.5%, designed to ensure that banks build up capital buffers outside periods of stress which can be drawn down as losses are incurred. If this buffer is eroded, the bank is subject to automatic restrictions on dividends, share buybacks, and staff bonuses to conserve capital;

- Countercyclical Buffer (CCyB) set by national regulators, generally close to 0% but potentially as high as 2.5% depending on the credit environment; and

- G-SIB Buffer between 1% and 3.5% of RWA, depending on the specific bank's systemic importance.

Let’s illustrate this with an example, to show how Basel III determines core capital requirements. Assume a systemically important bank has total risk-weighted assets (RWA) of €500 billion.

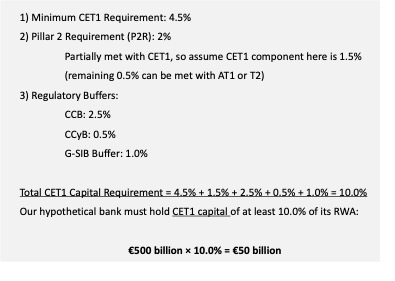

To determine the minimum total CET1 capital requirement for our hypothetical bank, we sum the relevant components:

The importance of Basel III to the healthy functioning of both the European and US banking systems

Drawing on lessons learned from the financial crisis, Basel III established a robust and more standardised framework for setting minimum capital requirements for banks, while maintaining sufficient flexibility for unexpected events. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, Pillar 2 capital requirements (P2R + P2G) were relaxed in certain cases to accommodate additional short-term market stresses placed on otherwise healthy banks. The Basel III reforms significantly expanded the universe of banks able to utilise Risk Sharing Transactions to further optimise their capital requirements.

In July 2023, just months after the collapse in quick succession of several US regional banks, the Federal Reserve Board, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) jointly released a proposal to implement Basel III Endgame standards, with certain additional, more stringent requirements, into the US bank capital rules.

Applying to banks with $100 billion or more of assets, the proposed new rules would significantly curtail the use of internal models to measure credit risk, force more banks to include unrealized losses and gains from certain securities in their capital ratios and change the method for calculating the additional capital requirements for US G-SIBs. By the regulators’ own estimates, implementation of the proposals could result in an aggregate 16% increase in CET1 capital requirements across the sector, much of that being felt by the very largest banks. Although significant dissent by certain senior principals within the regulatory agencies and strong pushback from Wall Street means that, for now, we can only guess whether the regulators’ next response will be a final set of rules or a fresh round of proposals, the RST market has seen a marked increase in issuance by some of the largest US banks since the announcement of the new bank capital proposals.

Having explained in Part 1 what RSTs are and in this Part 2 the regulatory framework which underpins and facilitates them, we can now turn our attention to the economic rationale for the banks that utilise RSTs as a tool for optimising regulatory capital. This will be the focus of Part 3 of this four-part series on Demystifying Bank Risk Sharing Transactions.

For more information:

Email: laurie@christoffersonrobb.com